Forget Kant, Mill, and Aristotle. Calvin (the mischievous boy, not John) and Hobbes (the tiger, not Thomas) are the modern era’s philosophers. I devoured C&H as a kid and have found that far from becoming less relevant, the comic strip had become more so.

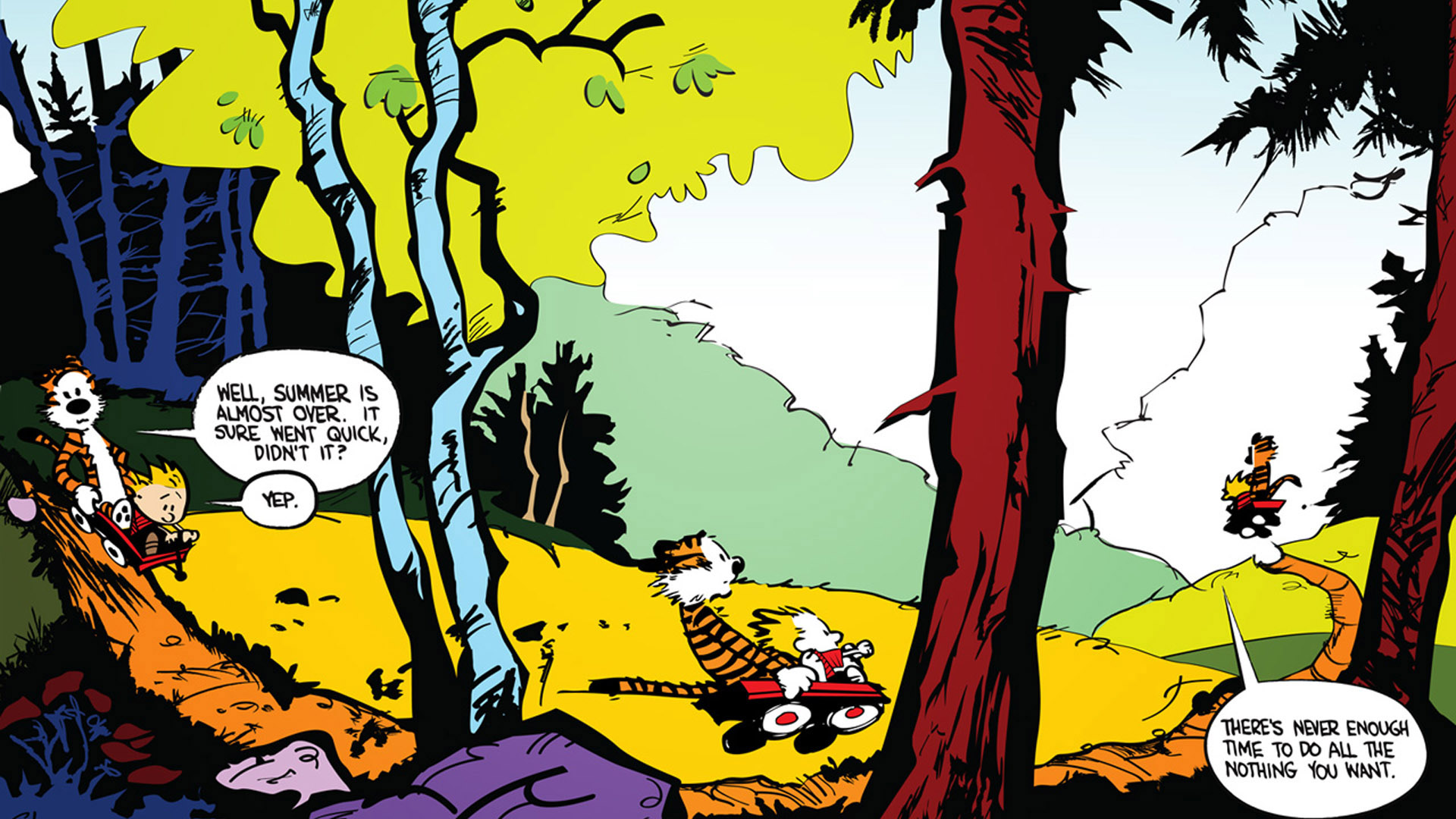

To illustrate why, let’s look at one of my all-time favorites:

Replace “summer” with “three month trip through South America”. Well, I suppose summer is almost over — let’s keep it as is.

I got to the sleepy town of Salento after trekking through the jungle in northern Colombia for five hot, sticky, tough, but rewarding days. I quickly decided that I was ready for a change of pace.

There’s a tendency when traveling to want to chase after the next adventure. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, but I have a hunch that Calvin is on to something. Sometimes we need a whole lot of nothing and there never feels like enough time for it. In Salento, I was going to make time for it.

It’s easy to forget that when the world is racing so fast that there’s a quiet story unfolding patiently in the background. I decided that I was going to stay still and try to watch it. So, after I did a much anticipated tour of a coffee finca and a beautiful hike in the Valle de Cocora, I settled into the nothing.

Boy, did it feel good. I would wake pretty early and grab a mug of fresh coffee from the nearby finca. Sometimes I would just sit with the cup and sip contently. Often I would read, and, if the mood struck me, write.

After a long stretch of missing my daily meditation practice and trying to find mindfulness in other ways, I found the space to begin again amidst the nothing. I moved a chair to a nice spot with a view of the valley and sat there often, rhythmically breathing in and out in a powerful yet simple ritual.

At some point in the morning, I would migrate to the hammock and carry on as before: coffee, reading, writing. Every once and a while, I would just lay back. Do nothing.

Later, I would get lunch. As the coffee was the only thing to sustain me in the morning, I was normally pretty hungry. I found a regular spot that would only have two sets of three options:

trucha / pollo / chorizo

verduras / frijoles / espagetti

It came with soup, a small banana, fresh juice, rice, salad, two different type of fried corn, and plantains. It was a no-frills spot and always delicious, and quickly my favorite became favorite trucha and frijoles. I tried to eat slow and enjoy all the flavors.

After lunch I would often walk up the hill and flights of stares to the Mirador - the lookout point. You could sit under the shade of a tree and look over the town in one direction and into the valley the next. It was a great place to do nothing.

Back at the hostel, I would grab another cup of coffee and settle in again. The afternoons were my favorite for thinking, and I spent a lot of time working through the next few chapters of my life (they’re currently only drafts). Soon enough, the light would be race to the horizon with the sunset and I would walk down the road to a raised hill and soak it in.

The evening would unwind quietly. I would go out for a small dinner - I was normally pretty full from lunch - and make awesome decisions like having a ice cream sundae brownie with peanut butter. Before I knew it, I would be ready to sleep. What beautiful days of nothing!

Some might view all this nothing as a waste, but I would beg to differ. I wrote that I wanted to travel to grow my soul, and I’m convinced that my soul grew in the quiet nothing those days in Salento. It’s almost like I had been filling it with so much experience these past months that it needed a moment to take it all in. When I get home, I have to remember that feeling of growth that pause gives. I have to make the space for nothing.